Discovering Israel — Part 2

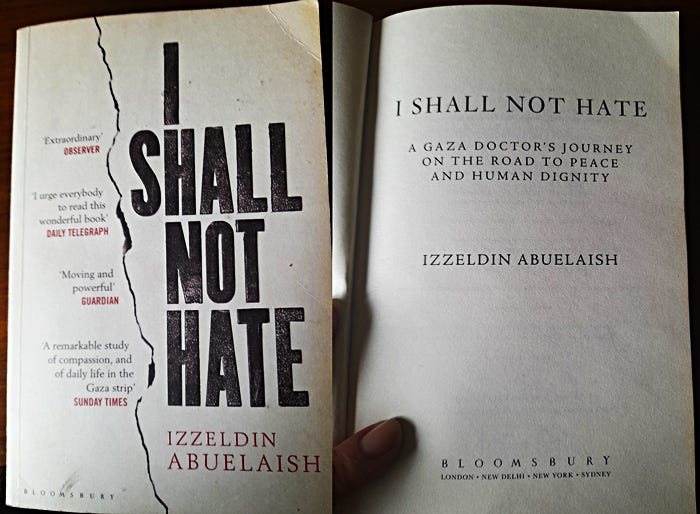

What I learned from the book: I Shall Not Hate by Izzeldin Abuelaish

This is yet another book that I read being part of the Merton PSC book club. We decided that after Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine (I wrote an article about this one and will add the link), we needed something easier to read, but still informative. And I Shall Not Hate was amazing.

If you feel like you were wronged by someone, and the sense of injustice is burdening you in every way, maybe even forcing you to question your faith in God or humans, this book is for you. Some people lose their faith after an accident or a natural disaster. This man still has his faith after the people who’ve been nothing but evil to him and his whole family for decades, yet he worked with them, helped them, those people still made him a target and murdered his 3 children in a brutal attack which they had the audacity to call ‘a mistake’.

So the story is a true account of Dr Abduelaish’s life. He keeps it very short, almost down to just the major events and experiences. And he has had many of those. His life reminded me of a song called ‘Ja Luzer?’ — Me Loser?

Especially the part ‘rodjen pod sretnom, zvezdom, magicnom, ali and ovom zemljom generalno tragicnom, cemu sam blizi, tri-put pogadjaj’ — born under a lucky, magical star, but above this, generally speaking, tragic country, what am I closer to, have a guess. To make matters interesting, this song is by a Serbia singsong writer who paid a price for being against the war in Bosnia.

While it’s easy to see Dr Abduelaish as a ‘luzer’, at least in the material-world sense, he’s anything but… It’s simply impossible to say that about someone who has such strength; such heart and mind. I may not always agree with him (I will get to that), however, it impossible not to respect him.

He starts his story with his incredibly difficult childhood. I don’t want to give away too much, read the book yourself, but I will say this: How did the world allow someone like Ariel Sheron to be a repeated offender? Do we have no thought for the victims?

Author’s youth is perhaps best defined by this quote:

Page 51: “I remember the June day when the results for the final exams for all grade six students in Gaza were supposed to be announced; it was the day the Six Day War started. At first I was more upset about not hearing the results of my exams than about having to endure a war.”

He becomes a doctor, so no surprises with respect to his exam results, however, it was far from being as simple as getting the results and going to uni. In his life, there were more complications, more obstacles and hardships to overcome.

In his adult life, I was surprised by his almost romantic view of Israel. I understand that he’s an exceptionally good person, and that he has met some decent Israeli citizens, but this borders on blindness. Maybe I’m wrong, however, after the Israeli army murdered three of his children, he was leaving Gaza with his surviving kids and he says:

Page 206 “I was concerned that the first Israeli they would see would be a soldier at the Erez Crossing, which is not in keeping with the lessons I taught them about who Israelis are.”

Page 210 “…she had internalized what I had always tried to teach all of my children: that Israelis are our friends and we should love them as we love one another.”

With all due respect, and this man is due a lot of respect, I must question why would he teach his children that? Israel is the master of its truth. We can either tell it or hide it. But if Israel can’t be bothered to stop killing innocent people, to stop tormenting Palestinians in every way it can, we should not put effort into hiding that about Israel. After all that he and his family had been through because of Israel, this is far from the truth even when we take his good nature and good Israelis into account. It seems like a desperate attempt to build peace by letting go of the past. While many think this is the way, I am certain that justice is the only way. Justice and truth are married. You divorce those two, you are left with nothing. In Bosnia, the war of the 90’s wouldn’t have happened if the parties who carried out atrocities during World War 2 were held to account. They were not, so they continued to make plans to achieve their objectives. They are still not held to account, so we can still expect them to plan and try to achieve the same goals they’ve always had — murder innocent people. And you can’t live with someone who wants you dead. When someone wants you dead, there is no compromise. This should be clear. Would both sides be satisfied if we all became zombies or something? We should all be 100% certain that we understand this as a fact. Life and death can’t coexist. It’s one or the other. Make your choice.

Add to that a very simple fact of life that chaos is created by only one side. Peace is our natural state, and it only needs us to stop creating chaos. We stop causing chaos, we have peace. But as soon as just one person decides to create chaos, peace is disturbed. If a country, with an army, is inclined to chaos, peace cannot be achieved until that country is held to account. This does not mean ‘every Israeli is to blame’. As I said many times before, collective punishment is insane. However, a country is more about a system than about its people. Israel needs to be held to account. It is as simple as.

What I am seeing here (and again, I might be wrong) is that the author was exercising collective reward. It’s not psychotic like collective punishment, but it is also not right. And the author has put a lot of effort into making us understand that some Israelis are lovely people. I have no doubt that that is true. However, the author also wants us to believe that most Israelis are nice. Err, I’m looking at the polls. Best case scenario: most Israelis are uninformed. This is as far as I’m willing to go. Though I should mention that when a group passionately supports collective punishment because they are afraid, and their fear is ‘inherited’, passed on from ancestors (i.e. they didn’t have any bad experiences themselves, but they’ve heard many stories), I believe people in such groups need therapy not guns. And while to some this might sound harsh, I’d like to mention that I apply this to all groups (my own included) and there are many groups that agree with this and do not think it’s harsh. Many people think this is reasonable. After all, face your fears without giving a whole bunch of other people better reason than yours to be afraid of you.

In short, I’m not sure if the author is using collective reward to steer away from collective punishment. Or perhaps he’s trying to be the best human he can be in hope to wake humanity on the enemy side and inspire them to stop causing chaos. I’ve seen this a lot with victims of dehumanisation. It’s almost like they feel they need to be the best of humanity to deserve life.

And, let’s be honest, though the Zionists were encouraged to go to Palestine to ‘humanise’ the local population, they have done the very opposite of that. The fact that so many Palestinians are not pure savages is more about their response to this dehumanisation, which, according to the author (page 47) “The Palestinian mother is the author of the survival story of the Palestinian people.”

This sentence moved me to my core, as did a number of other things Dr Abuelaish said about his mother, and women in general. But I’ll let you find out those for yourself. With this one sentence my mind wondered about mothers and how they all want their children to stay alive. But this doesn’t come to light until the life of their child is in danger. I’ve seen it in the war. During the war, mothers cared only about their child’s survival. Their motto was: Who cares about education, or dreams, ambitions, or anything else, just stay alive. And then the war ended, oh my goodness, we were right back to mothers who wanted good grades, clean clothes, healthy eating, balance between socialising and working, and all the other stuff that makes a life.

Someone made a documentary about dreams and ambitions of children in Gaza. They asked the children the same old question that kids are asked all over the world “What do you want to be when you grow up”. There were all kinds of typical replies: footballer, doctor, fireman, lawyer, writer, and so on, however, there was a shocker in there too. More than one child replied ‘we don’t grow up’. Around 50% of the population in Gaza are children. Yet, at the same time, they have one of the highest university graduate rates in the world.

So if we take all this into consideration, it is possible that the doctor’s romantic view of Israel is his way of proving he’s worthy of life, so that Israel would be shaken into respecting Palestinian life. As I said, I have seen it in other victims of dehumanisation. It is as if being a human isn’t enough, they have to prove themselves to be the kind of human that should deserve life. Let’s just say that if we all had to live like that, the world population wouldn’t be even 10% of what it is.

Look at this sentence for example:

Page 90 “But those soldiers knew me, and they ought to have dealt with me not as a Palestinian but as a human being.”

How can this be normal to any human being in the world? The stories of his childhood are heartbreaking. There was an incident with an errasor that made me wish we could just shower the whole Strip with school equipment. He worked his way from unbelievably hard circumstances to a person who had a job in an Israeli hospital delivering life into the world. How does a person do this, I don’t know. But he did it. Of course he assumed that he deserved some respect. And to be honest, if this Palestinian wasn’t good enough for Israel, no human being is good enough for Israel. We need to face that fact.

And he wasn’t good enough. They targeted his family. I’m not going to tell you why that is so obvious, but I will tell you that anyone who has the audacity to claim it was an accident, in the face of all the facts, is a f-ing moron. Excuse my language. He was targeted even before Israeli army went into Gaza in 2009. He was already on their list, and nothing could have stopped them. When a fanatic gets an aim in mind, you can call all the TV stations you want, the fanatic will go ahead with their plan.

So the main lesson I took from the story is that Israel has no respect for human life. They will target the parson who has proved himself as an absolute gem, and if that wasn’t bad enough, they will also lie about it so that they can get away with it. Which also makes me think they believe the world is stupid. They insulted my intelligence by claiming this could have been an accident. And as for the way the mother of a soldier reacted to Israeli army murdering 3 innocent daughters of a doctor who brought life to Israel — SHOCKING!!! I wanted to jump into the book and beat the shite out of the coldblooded, selfish, arrogant bitch! My fury started on page 183, and by page 185 the pen I was using to make notes in the margins went through the paper. A woman like that belongs in jail. I’m sorry, but people who don’t show respect to others do not deserve to be shown any respect. And this is not one of those situations where we’re unsure. The man lost 3 daughters to targeted attack from the army where the woman’s brats serve. The bitch! I can’t help it. I am so angry. I don’t know how the author managed not to strangle her. He was probably worried about his other kids.

While that’s the main lesson I took from the story, there are other things I learned. I’ll go through some of those in ‘headline’ fashion as much as possible.

1. Palestinians are just like any other people. Most of us would react the way they do if we had to live the way they are forced to live. Some choose to fight back come what may, others just make do with what they have in that ‘this-will-all-end’ fashion, while some, like the author, will push themselves beyond all limits to achieve more.

2. Gaza has been around for some time.

Page 32–33 “The earliest recorded reference to Gaza is in Egyptian texts and refers to Pharaoh Thutmose III’s rule when Gaza was the main city of the Land of Canaan and the only overland route between Asia and Africa. Much of Gaza’s history comes from ancient stories told in the Quran, the Bible, and the Torah. The Philistines arrived in Canaan around 1180 B.C.E., during the Iron Age, and made Gaza a famous seaport.”

So we have, what, 3500 years worth of history, yet the whole mess is down to a bunch of Western politicians believing that a handful of Jews from Eastern Europe have the right to… drum roll please! RETURN!!! It is beyond laughable. If it didn’t cost (probably) over a million lives by now, it would be funny.

There is a possibility that these Western politicians are using Israel to get away with crime, but that would make them evil. Between evil and stupid, let’s just call them stupid.

3. Understanding survival under Israeli occupation. For me, this was the hardest thing to wrap my head around. It’s the details that we don’t even think about. We’ve all heard about the check points, but how they work was a surprise to me. The getting to one point, walking to another, getting your bags, being checked again. I had so many questions about these points. WTF do they serve? To humiliate Palestinians as much as possible? To give as many Israelis ‘a job’, and make some very pathetic humans feel very important? It is easier to visit a prisoner in Britain than to return home to Gaza.

Water — we turn the tap on, complain about the quality of water, we filter some, we buy bottled water, we shower, clean our clothes, our house, even our car. We don’t think about standing in line, at certain times of day to fill our buckets and take them home.

Having a car.

Shopping.

Going to school. BTW, I was surprised that Egypt didn’t treat Palestinians with a little more respect. But maybe that’s just me.

Even farming is an issue in Gaza.

Yet we expect Palestinians, or more specifically people of Gaza, to be just like anyone else in the world. In fact, I’ve heard complaints that Palestinians are not all that since they have no new inventions.

Page 47 “Survival doesn’t allow time for poetic reflection.”

This is what we need to understand. People of Gaza live in such circumstances that even survival is a great accomplishment. Hence, their level of education is a huge plus, much bigger than in a normal world. Furthermore, we also need to take into consideration that even if they did invent something, how likely is it that we’d find out about it? There are many inventions in the world that we don’t hear about until someone in ‘the right part of the world’ copies it. But that’s for another topic and another research. I just thought it might be worth a mention here.

All in all, everyday life in Gaza is a bit clearer to me now.

4. Generational gap is different in Gaza. The shared loss yet unshared view of the future.

Page 38 “Even now, six decades after my family became refugees in the Gaza Strip, knowing that our family land will never be ours again, I still suffer from the loss. However, I was never drawn in by the loss, nostalgia, and outrage my grandfather expressed. I learned instead to direct my attention to studying and surviving. I knew there was a better way, and even as a child, I set out to find it.”

5. The differences between Palestinians and Israelis was shocking. However, what’s even more socking is how much the author is putting forward an argument for ‘both sides’, with phrases like ‘heal our mutual wounds’, or ‘security is as important to Israelis as it is to Palestinians’, or ‘(should not see) all Israelis (as) occupiers and all Palestinians (as) troublemakers’, or ‘both sides led by extremists’…

Page 123 “We need to look at what’s possible right now: working toward both sides having more equal conditions, with equal rights and mutual respect.”

While this sentence sounds 100% right in any normal country, up to this point in the story we’ve learned that Israel controls everything, that life is hell for Palestinians, later on we’ll learn that even dead Palestinians are controlled by Israel, and not respectfully at all. In other words, for Israelis to have equal right to Palestinians, Israelis would need to loose a lot. Like, if we are talking about these two sides meeting in the middle, we’d have to take a lot from Israelis and give to Palestinians. I don’t think that’s what we want in the region. I think what we are talking about is Palestinians need our help. I.e. we need to give to Palestinians what the Israelis already have; like access to clean water, freedom to move, you know, things like that. So, NO! this is not about making the sides equal. We need to focus on Palestinians because they are in great need. They need to have what Israelis already enjoy.

‘Mutual wounds’ — I hear a lot about this in Bosnia as well. In a war, ALL sides have wounds. Bosnian war took the lives of various foreigners who got involved whether as journalists, UN peacekeepers, humanitarian workers etc. However, when we hear about ‘mutual wounds’, it is not about everyone killed, it is about Serbs and Croats who were killed. And there is pressure to make all sides equal in ‘suffering’. We’re not equal in suffering! When one side makes a bigger ‘song-and-dance’ about 10 people who were killed than about 1000 people who were killed on the other side, that’s dehumanisation. It’s not that the 10 don’t matter. They do matter. They matter very much, but not as much as 1000 people.

And when they fail to make their case for equal suffering in the last war, which they inevitably fail since the facts speak for themselves, they pull out tragedies from the past. Some of these are true, some false, but they will use all. And it is fascinating to see how often the Ottoman empire will be mentioned, yet the Austrio-Hungarian will not be, let alone the era called ‘the kingdom of Yugoslavia’. You’d think these two didn’t kill anyone at all. However, that’s not the point. The point is to change the subject and get the world to hear about ‘their suffering’. The main point is to make people all over the world see that they have suffered. On the one hand, this is used to get sympathy, on the other it’s used as a ‘we have the right to cause suffering’. We need a world where no one ever has the right to cause suffering.

In short, for me, when someone mentions ‘mutual wounds’ in a war, I get all sorts of alarm bells ringing in my head. While ‘mutual wounds’ are a fact of every war, they never ever imply any level of equality or equal suffering, let alone a right to cause harm.

And I’ll end this point with a quote that I think best shows the reality of the situation.

Page 177–178 “The apartment (their home) was full of the dead and wounded. Shatha was standing in front of me, bleeding profusely. I was sure that Ghaida had also been killed as there were wounds on every single part of her body and she lay still on the floor. Nasser had been struck by shrapnel in the back and was also on the floor. I wondered who could help us, who could get us out of this catastrophe. Then I realised I still had a connection to the outside world. I called Shlomi Elder, but the call went to his voice mail. I left a message: “YaRabbi, YaRabbi-my God, my God-they shelled my house. They killed my daughters. What have we done?” All I could think was: this is the end. This is the end.

In the meantime, my brother Atta’s wife, Sanaa, had attached a white flag to a pole and had left the house to find help. Nasser’s wife, Akaaber, went into the street with her. They walked to the refugee camp two and a quarter miles away and told the people what had happened. Despite the colossal danger in the street, the people from Jabalia all came: our friends, old neighbours, the Palestinians we had grown up with and struggled for survival with. They came with stretchers and blankets, pushing boldly past the soldiers and tanks, to help my family. It took them about fifteen minutes to get to the house.”

The two sides are painfully different in this account. Plus, who is ‘WE’ in the voice message he left to Shlomi Elder? He says “What have we done?” Who is we? I’m not seeing ‘we’, I am seeing the killers and the dead — there is no ‘we’ as far as I can see.

6. Politics! This is the last point I will mention. This article is already much longer than I thought it will be. But I feel this has to be mentioned.

The author did run for elections in Gaza. He was surprised by how the voting turned out. Sure, it might be the case of changing allegiances, and self-destructive behaviour that he mentions at the beginning of the book. This is not surprising. If people do not believe in ‘long-term’ they will make decisions that are best in the ‘short-term’ and send the ‘long-term’ to hell. However, and I’ll once again borrow from what I’ve learned in Bosnia, elections can be just a show. We once found a car that picked up the box of ballot papers loaded with identical boxes. One set of boxes could have been easily replaced by another. But then, democracy is about so much more than voting. So I’ll leave this point here.

The story is very easy to read in terms of language, structure and plot. It is heart-breaking in terms of content. How much pain and suffering can one person be expected to handle in one lifetime? Yet Dr Abuelaish didn’t just handle the pain, he fought against it to become a doctor, work in an Israeli hospital, and fight for peace in Palestine.

I’ll add just one more PS sort of note: Ben-Gurion University (page 89) plays a big role. The name of the university shook me. Ben-Gurion was the mastermind behind the ethnic cleansing of Palestine in the 1940s. If it wasn’t for that, the author would have had a normal life. The torment this man and his whole family faced was down to ‘Ben-Gurion’. I know Serbs and Croats honour their war criminals, so it’s not news to me. But the scale of this honour in Israel is greater than any I’ve seen in Bosnia. How do we move into a safe environment for every person in the region if mastermind of ethnic cleansing is honoured like this?

Discovering Israel — Part 1

What I learned from the Book: Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine by Ilan Pappe